You may have seen mention in the media of the introduction of separate meningococcal vaccination programs in South Australia and Western Australia – they’re being implemented in response to a number of outbreaks of meningococcal disease in those states. The South Australian Health Department, together with the University of Adelaide and vaccine manufacturer GSK, have announced that they are offering the meningococcal B vaccine to 60,000 adolescents in grades 10, 11 or 12 from 2017. Testing has proved the B strain to be responsible for 19 of the 24 meningococcal meningitis cases this year in SA. While WA is providing a one-off administration of the vaccine that protects against the W strain in a program directed at children and young adults (aged four years and under and 15 – 19 years of age) living in Kalgoorlie, Boulder, Coolgardie and Kambalda - 5 cases caused by the W strain have occurred in Kalgoorlie in the past 2 months.

What do we know about this life-threatening illness?

Neisseria meningitidis (a meningococcus), is a leading cause of bacterial meningitis, producing sepsis (blood poisoning), pneumonia and other localised infections3. We know it causes death in around 1 in 20 of individuals infected1,2 in high-income countries, and several times higher in developing countries. Further, approximately half of all survivors have neurological complications, including hearing, visual or cognitive impairment1, loss of fine motor skills, seizures, hydrocephalus and limb amputations due to tissue cell death3.

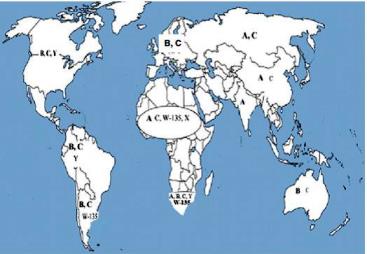

There are 13 serogroups of Neisseria meningitidis but most human disease is caused by only 5 of them - A, B, C, W & Y4. Meningococcal bacteria can live harmlessly in our throat and nose; around 10% of people will be colonised by these bacteria at any one time without ever becoming ill – they are ‘healthy carriers’. It isn’t completely understood why in some people these common bacterial colonisers are able to evade the body’s natural defences and cross the blood-brain barrier to cause meningitis1. There are, however, several risk factors which increase susceptibility, including: specific age groups, medical conditions causing lowered immune defences and genetic factors1. When it comes to someone transmitting the bacteria to another person, this is more likely to occur in smokers (higher incidence of being a carrier), in those people with close contact (i.e. with saliva, such as during coughing, kissing or sharing eating utensils) or living in the same household. You can’t catch the bacteria through casual contact or, unlike measles, from merely being in the same room as someone with the infection1.

Australia and Meningococcal Meningitis

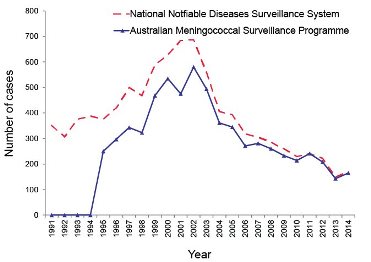

From the 1950s, serotypes B & C were responsible for most disease recorded in Australia, but, with the introduction of the C strain vaccine into the National Immunisation Program in 2003, the incidence of meningococcal infections due to this serotype dropped from 3.5 cases per 100,000 in 2001 to 1.1 per 100,000 in 2011. Subsequently the majority of IMD cases in Australia have been due to the B strain5.

Statistics available for 2016 show that Victoria has had 57 meningococcal meningitis cases this year to date - up from 50 cases in 2015 and 26 cases in 2014. In New South Wales there have been 63 cases so far in this year, with 43 in 2015 and 35 in 2014 (of which 39 cases were not strains B or C). In WA numbers have been static from 2014 to 2015 with 17 cases annually and usually only 1 to 2 W strain cases, but there have been 20 cases this year with the W strain accounting for 12.

In Australia, the disease has a peak incidence during the cooler months of winter and early spring, but smaller outbreaks also occur at other times. Age groups with the highest incidence of disease are under 4 years and again, to a lesser extent, between 15 and 24 years of age5.

Number of invasive meningococcal disease cases reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System compared with laboratory confirmed data from the Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme, Australia, 1991 to 20145.

Global incidence

It is estimated that there are approximately 1.2 million cases of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) causing approximately 135,000 deaths across the globe each year. The world-wide burden of IMD varies by region: countries are grouped into ‘high, moderate and low-incidence’ and Africa falls into the first category by virtue of the frequent epidemics that occur in 25 countries of sub-Saharan Africa - the so-called ‘meningitis belt’. These epidemics strike during the dry season (Dec-June)6, alternating with an endemic incidence during the rainy season (June-Oct)7.

Distribution of common and predominant meningococcal serogroups by region. Predominant strains are highlighted in bold text3

Population Health Metrics 2013, 11:17

Available vaccines

Vaccines used to protect against meningococcal meningitis disease in Australia come in 2 forms – one cannot be used under 2 years of age, is shorter-acting and will not eliminate the bacteria from the individual’s respiratory tract (polysaccharide vaccine), whereas the other covers a wider range of ages, has a longer duration and reduces nasopharyngeal carriage of the bacterium (conjugate vaccine).

The Australian National Immunisation Program provides one dose of serogroup C vaccine (in combination with Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)) to infants at the age of 12 months8. Another, a meningococcal B vaccine, is available on the private market so is without government subsidy at this time.

So the 4 formulations of meningococcal vaccines currently available for use in Australia8:

- Meningococcal C conjugate vaccines, also in combination with Hib

- Recombinant multicomponent meningococcal B vaccines

- Meningococcal A, C, W135 and Y conjugate vaccines

- Meningococcal A, C, W135 and Y polysaccharide vaccines

Travel and meningococcal meningitis

Specific itineraries that are more likely to warrant the recommendation of the meningococcal vaccine are:

- Travel to the meningitis belt in sub-Saharan Africa

- Annual Hajj pilgrimage and Umrah (the ACWY vaccine is a requirement for entry into Saudi Arabia)

- Travel to a region with a current outbreak of IMD

- Young people travelling in groups or living in dormitories i.e. at college

- Extensive close contact with the local community in regions of high IMD incidence

- Some medical conditions, including functional or anatomical asplenia, HIV infection and haematopoietic stem cell transplant.

As always, the final decision on what is best for any traveller will be decided during a pre-travel consultation with a medical practitioner.

For more information please call Travelvax’s travel health advice line on 1300 360 164.

1. Adriani, K.S, Brouwer, M.C., & van de Beck, D. (2015) Risk factors for community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine (73:2) p.53 – 60. Accessed 20.12.16 Available at: http://www.njmonline.nl/

2. Van de Beek, D., Brouwer, M.C., Thwaites, G.E. & Tunkel, A.R. (2012) Bacterial meningitis 2 – Advances in treatment of bacterial meningitis.Accessed 20.12.16 Available at: http://www.researchgate.net/

3. Jafri, R.Z, Messonnier, N.E., Tevi-Benissan, C., Durrheim, D., & Eskola, J. et al. (2013) Global epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease.Population Health Metrics (11:17) Accessed 20.12.16 http://www.pophealthmetrics.com/

4. Halperin, S.A, Bettinger, J.A, Greenwood, B., Harrision, L.H., & Jels, J. et al (2012) The changing and dynamic epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Vaccine (30S) p.B26-B36. Accessed 20.12.16 Available at: http://www.researchgate.net/

5. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Meningococcal Disease Factsheet July 2015. Accessed 20/12/16 Available from: http://www.ncirs.edu.au/

6. Department of health Meningococcal (2014) Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme annual report (40: 2). Communicable Disease Information. Accessed 20.12.16 Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/

7. Koutangani, T., Mainasara, H.B., Mueller, J.E (2015) Incidence, Carriage and Case-Carrier Ratios for Meningococcal Meningitis in the African Meningitis Belt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One (6) Accessed 20.12.16 Available at: http://journals.plos.org/

8. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th edition, 2013. Canberra: DoHA; 2013. Meningococcal meningitis. Available at: http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/

9. US CDC Health Information for International Travel 2016 (Chapter 3. Infectious diseases related to travel – Meningococcal Meningitis) Accessed 20.12.16 Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/