The inflammation of the stomach and intestines, known as gastroenteritis, is typically caused by a virus, bacterium or a parasite. What we know as food poisoning is a common cause of gastroenteritis when the ingested bacteria, viruses or their toxins – known as pathogens - have contaminated food in high enough numbers to establish an infective dose.

Some toxins are found naturally in foods, but in many cases we become infected through direct faecal/oral contamination (person-to-person, possibly from an asymptomatic contact) or from the environment (from animals or via contaminated surfaces), but the symptoms are the same even if food isn’t involved. Food poisoning may also result from ingestion of food containing chemicals, heavy metals, parasites or fungi.

Parasitic infections causing gastroenteritis are commonly contracted through contaminated water, infected soil or person to person from lapses in sanitation and hygiene. The severity of the infection can be directly influenced by a weakened immune system, a person’s age (more likely in the frail, very young or elderly), during pregnancy or when taking medications such as those that reduce stomach acidity (PPIs).

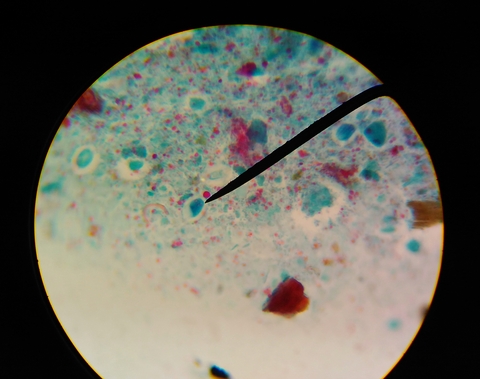

Parasitic gastroenteritis

Giardiasis and Cryptosporidiosis are parasitic infections of the intestine contracted through person-to-person contact in settings such as households and child care centres. These microscopic organisms can be found in the faeces of infected humans and animals and are spread when hands are not washed after going to the toilet or changing nappies, on drinking or swimming in contaminated water, handling infected animals or eating food contaminated by an infected person.

Symptoms of infection with Giardia parasites can appear between 3-25 days and typically include diarrhoea, stomach cramps, bloating, nausea, loose and pale greasy stools, fatigue, and if symptoms continue, weight loss. Some infected people have no symptoms, however they can still pass the parasite to others. The infection can last for months if left untreated.

The most common symptom of Cryptosporidium infection is watery diarrhoea. Symptoms appear between 1-12 days (usually 7 days) of infection and may come and go, lasting days to weeks. People with a weak immune system may have more severe symptoms that can last for months. A person is most infectious when they have diarrhoea, but infection is still possible for several days after symptoms disappear, while the parasite is still being excreted.

Food poisoning - Common causes in Australia

Our strict national food safety standards are legislated by the federal government and they encompass food handling, health and hygiene requirements for food handlers, conditions for food businesses and cleaning, sanitising and maintenance. Even so, it has been estimated that more than 4 million Australians suffer from a bout of food poisoning every year. And the source? Could have been from a home-cooked meal or when dining out. (If you suspect you have food poisoning, in particular from a food outlet, it is important you report your illness to your local council or the Department of Health, so that the cause can be investigated).

The majority of Australia’s food poisoning cases stem from bacterial causes and we all need to be aware of the temperature range, the danger zone for our food, where most bacteria will grow - between 5°C and 60°C.

Bacterial

- Salmonella – Salmonellosis, or infection with salmonella bacteria, is spread through contaminated foods, but it can also be acquired through contact with an infected person or carrier. There are more than 2,000 types of salmonella bacteria (which include the causes of typhoid and paratyphoid fever). Symptoms which include fever, diarrhoea (possibly bloody), cramps, nausea and vomiting, generally present from several hours to several days after infection and last for up to a week. Serious systemic illness can occur if the bacteria cross into the bloodstream and this may require hospitalisation and antibiotic therapy. Salmonellosis is mostly associated with poorly cooked poultry, cross-contamination of other foodstuff from raw poultry, and dirty or cracked eggs.

- Campylobacter – This is one of the most commonly notified causes of bacterial gastrointestinal illness in Australia, with cases more than doubling from 2013 to 2019. In fact, Australia has some of the highest notification rates among high-income countries. The bacteria can be carried in the intestines, liver and other organs of asymptomatic farmed animals (chicken, cattle and pigs) and meat may be contaminated during slaughter. From an incubation period of 2 to 5 days after ingestion of the bacteria, symptoms such as fever, diarrhoea (often bloody), stomach cramps and nausea begin. There can be complications which include septicaemia, Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis and urinary tract infection. Campylobacteriosis is frequently associated with the consumption of poultry and raw milk, and is more common in the warmer months.

- E. coli - Escherichia coli are a large group of bacteria normally found in the intestines of people and animals. Some strains are harmless and are actually necessary for a healthy, functioning gut. There are, however, other toxic strains that can trigger a gastric illness which in around 10% of cases (particularly in kids under 5yo) can develop into a serious, potentially fatal complication - haemolytic uraemic syndrome, with the potential for kidney damage and failure. For most cases of E. coli food poisoning, symptoms appear from 1 to 10 days after ingestion – they include fever, fatigue, sudden onset of severe watery diarrhoea, nausea and cramps – which usually settle after a week or so. Toxic E. coli strains are more likely to be contracted from meat, unpasteurised dairy products, fruit juice and unwashed raw fruit and vegetables, through animal contact and also person-to-person.

- Listeria – Infection with listeria (listeriosis) is a rare but serious bacterial disease. The organisms grow on certain high risk foods and are unusual in that they will grow in cold conditions, such as in the refrigerator. The incubation period ranges from a few days up to almost a month after ingesting the bacteria and develops into in a flu-like illness (i.e. fever, chills, nausea, diarrhoea and muscle aches). There is a higher likelihood of complications, such as meningitis and septicaemia, in the elderly and in immunocompromised people. Listeria infection is associated with miscarriage in pregnant women or the death of newborn babies. Outbreaks of listeriosis have stemmed from contaminated rockmelon and ready-to-eat foodstuffs such as delicatessen meats, raw milk, soft cheeses, soft serve ice-creams, pre-prepared salads, unwashed raw vegetables, pâté, cold diced chicken and pre-cut fruit and fruit salad. The infection is not spread from person-to-person.

Viral

• Norovirus – aka gastric or stomach flu, winter vomiting or viral gastro, it is a highly contagious gastroenteritis-causing virus which is spread on contact from an infected person via food, surfaces and objects or person-to-person contact, including via aerosols. A single infected person can shed literally billions of norovirus particles and it takes as few as 18 particles to infect another person. Winter is the peak season for norovirus, the most common cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Infection generally resolves within 24-48 hours without treatment, but dehydration is a common complication, especially among the young, people with chronic diseases and the elderly, and they are likely to get a more severe bout of sickness. Illness can persist for significantly longer in people aged 70 or older, probably due to their diminished immune response. Good hygiene practices are important to prevent the spread of norovirus – washing with soap and warm water for a full 20 seconds is the best preventive measure, and stay home if you are sick. Norovirus is particularly likely to spread through areas of shared food – among families, childcare centres, schools, aged care facilities and cruise ships.

• Rotavirus – Recognised as the most common cause of severe and life-threatening diarrhoea in children in Australia because it can lead to dehydration, shock and sometimes death. It is a highly contagious disease that is transmitted person-to-person through contact with someone infected with the virus or via contaminated food, surfaces and objects. Rotavirus vaccination: Before the rotavirus vaccine was introduced in Australia in 2007, each year around 10,000 children under 5 were hospitalised and at least 1 child died. Since the vaccine’s inclusion in our routine childhood immunisation program, hospitalisation rates dropped by more than 70%. The timing of administration of oral rotavirus vaccine courses depend on the brand: either 2 or 3 doses which are given by 24 weeks of age. Serious reactions to the rotavirus vaccine are rare.

• Hepatitis A – In recent years, hepatitis A infection rates among the wider Australian population have been low, with only sporadic notifications usually caused by common food-borne sources or in overseas travellers returning from countries or regions of high or intermediate endemicity. A marked exception was among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who had 4-fold higher incidence of Hep A. Hepatitis A vaccination was made available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 12-24mo in areas of QLD, South Australia, Western Australia and the NT in 1999 and its introduction, along with ensuring a supply of clean water, sewerage and improved hygiene, has led to a decline in Hep A notifications which are now closer to rates in the non-Indigenous community. The virus is transmitted through contaminated food or water, or direct contact with an infectious person (including through some forms of sexual contact). For information of hepatitis A in travellers, go to: https://www.travelvax.com.au/holiday-traveller/vaccinations/hepatitis-a

Bacterial & other toxins

- Staphylococcal aureus – This bacterium might live relatively harmlessly on the skin or in the nose of many people, but when left to grow on foodstuffs, it can produce a toxin. The gastro illness caused is characterised by a rapid onset of symptoms such as vomiting, cramps and diarrhoea from 30 minutes after ingestion, and recovery is between 1–3 days, rarely causing death. Most common transmission is from food handling, especially with foods requiring hand preparation such as salads and sandwich fillers.

- Bacillus cereus - is generally found in soil, dust and spices and there is an increased risk of bacterial growth if prepared food (especially those containing starches such as rice, pasta or potato) is stored without good refrigeration for several hours before serving. The heat-resistant spores produce 2 types of toxins, depending on when they were formed, that cause either a vomiting or diarrhoeal illness. The incubation period of the vomiting syndrome is the shorter of the two, however both illnesses are generally mild in healthy people with recovery usually in 24 hours. It is possible to be infected with the 2 toxins at the same time. Bacillus cereus infects approximately 3,350 people in Australia each year.

- Clostridium perfringens – This type of bacteria is widespread as it’s found in the intestines of people and animals, on raw meat and in dust and soil. In the unsafe ‘danger zone’ temperatures, it can multiply and, when swallowed, produces toxins that cause a diarrhoeal illness. Symptoms of cramps and diarrhoea usually develop rapidly anywhere from 6 to 24 hours after eating the tainted food and subside in under a day. Foods at higher risk of contamination include meat and poultry, thickened sauces and pre-cooked foods, particularly if cooked in large batches and also if they are spiced and herbed.

- Ciguatera – Ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) is the most common non-bacterial illness related to seafood worldwide, with the average incidence in Australia estimated at 148 cases per year. The toxins are produced by marine micro-algal species ingested by herbivorous fish, which are then eaten by larger carnivorous fish. As these fish are eaten by larger reef fish, these toxins become more concentrated. So the risk of poisoning is greatest when consuming larger reef fish. There is no process to remove the toxins from the fish and cooking or freezing the fish will not destroy the toxins. Symptoms can range between a combination of gastrointestinal, neurological and cardiovascular effects. Gastrointestinal symptoms may be nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and stomach cramps, and neurological effects may be tingling and numbness in fingers, toes, around lips, tongue, mouth and throat, burning sensation, joint and muscle pains and weakness. An unusual symptom is temperature reversal sensations –where hot or warm objects feel cold, and cold objects may feel warm. Fatalities are rare. In Australia, the majority of outbreaks are from fish caught in Queensland and the Northern Territory, predominantly from Spanish mackerel, in other states the cases have been linked to imported fish from tropical national and international regions. Fatalities are rare.

Causes

Food poisoning-causing bacteria can multiply rapidly if conditions are ideal. These include:

- Temperature – as mentioned above, the temperature ‘danger zone ’is a range between 5°C and 60°C. Perishable food needs to be kept either very cold or very hot.

- Water – bacteria need water for growth, which is why dried foods are less likely to harbour pathogens.

- Time – in ‘danger zone’ conditions, one bacterium can multiply to more than two million in seven hours.

Contaminated food will usually look, smell and taste normal.

Prevention

It is important to use food safety guidelines when preparing, storing and serving food.

- Keep it clean – good hand hygiene is vital when handling food

- Separate raw food from cooked food during storage

- Use separate food preparation surfaces and knives for meats

- Keep it cold – below 5°C

- Keep it hot – above 60°C

- Check the use by date

High-risk foods include:

- raw and cooked meat

- dairy products

- eggs and egg products

- smallgoods

- seafood

- cooked rice and pasta

- prepared salads

- prepared fruit salads

- some wild mushrooms

Symptoms

The symptoms of food poisoning will vary depending on the type of organism causing the illness and their onset may be almost immediately after ingesting the food, or begin a few hours later, lasting from 24 hours to up to 5 days.

One or more of these common symptoms may be experienced:

- stomach cramps

- nausea

- vomiting

- diarrhoea (may have bloody stools)

- fever

- headaches

Treatment

Most people don’t need to see a doctor for food poisoning unless they fall into the higher risk groups when serious symptoms and outcomes are more likely to occur, such as miscarriage, meningitis, kidney failure and death. These groups include:

- elderly and frail

- children under 5 years

- pregnant women

- people with underlying illness or chronic diseases

Dehydration

Dehydration is a serious effect related to food poisoning and fluid must be replaced to aid in recovery. Sucking ice and/or frequent sips of water is important along with the use of oral rehydration salts, such as those available commercially. If not, adding six teaspoons of sugar and one teaspoon of salt to one litre of water is an alternative. Avoid any medicine that prevents vomiting or diarrhoea, unless advised by a doctor. Some common, over-the-counter diarrhoeal medications cannot be used in children, so seek advice from your doctor or pharmacist.

Full recovery for most people is within 2-5 days and antibiotics, while generally not required, may be prescribed for people in the higher risk groups.

When to seek medical advice:

Children:

- Your child has symptoms and is less than 1 year old

- Your child has severe stomach pain and vomiting and can’t keep fluid down

- Your child has signs of dehydration, wont drink and has little or no urine output

- You are worried your child appears extremely unwell

Adults:

- You still have symptoms after 3 days, or your symptoms are very severe

- You can’t keep any fluids down after 24 hours

- There is blood or mucus in your vomit or diarrhoea

Under the ‘Travellers’ diarrhoea’ tab on the Travelvax website we have covered a number of other causes of food poisoning which are more common in developing countries.

References:

- Australian Food Standards: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Documents/Bacillus%20cereus.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health: https://www.aihw.gov.au

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: Link between stomach acid medications and gastrointestinal infections - expert comment. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/news/2017/study_link_stomach_acid_medications_gastrointestinal_infections_expert_comment.html#:~:text=The%20research%2C%20led%20by%20University,common%20causes%20of%20food%20poisoning.

- Better Health Victoria: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/HealthyLiving/food-poisoning-prevention#highrisk-foods

- Food Authority of NSW: https://www.foodauthority.nsw.gov.au/consumer/food-poisoning

- Food Safety News: Publisher's Platform: Pathogen information at your fingertips on our 'bug' sites | Food Safety News

- Health Direct: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/food-poisoning#what-is

- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, Number of notifications of Campylobacteriosis, Australia: http://www9.health.gov.au/cda/source/rpt_3.cfm

- Foodborne Pathogens and Disease: Vol 17, No 5, 2020; Characteristics of Campylobacter Gastro-enteritis Outbreaks in Australia, 2001 to 2016: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/fpd.2019.2731

- Aust Government, Department of Health: Appendix 2: Public fact sheet on norovirus gastroenteritis: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-cdna-norovirus.htm-l~cda-cdna-norovirus.htm-l-app2

- Travelvax Australia: This winter virus can sink your holiday, April 4, 2016: https://www.travelvax.com.au/latest-news/winter-virus-can-sink-your-holiday

- Vaccine, Volume 35, Issue 1, 3 January 2017; Impact of the national targeted Hepatitis A immunisation program in Australia: 2000–2014: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X16310210

- Food Standards Australia NZ; Bacillus cereus: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Documents/Bacillus%20cereus.pdf

- World Health Organisation: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety

- Travelvax resources – Ciguatera Fish Poisoning