By Dr Eddy Bajrovic, Medical Director of Travelvax

A colleague told me how she had managed to get typhoid fever while working at a holiday resort in Mexico back in the early 1980s - one meal taken in the nearby town proved to be her undoing. But after two week’s rest, a simple course of oral antibiotics and countless banana sandwiches (the only thing she could stomach and hasn’t been able to eat since), she recovered. Fast-forward thirty-five years and treating typhoid fever has become much more problematic after new, resistant strains of the bacterium appeared and then started to spread.

Infection that is exclusively ours

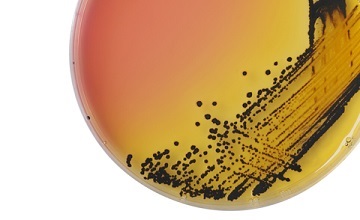

Only humans can contract typhoid fever. Caused by a bacterium, Salmonella enterica serovar typhi (S. typhi), it is one of the enteric fevers – there are three others caused by paratyphoid bacteria (S. paratyphi serotypes A, B and C). Typhoid is a severe systemic infection that can produce symptoms such as abdominal pain, rash, headache, malaise, coated tongue, as well as sustained fever and either diarrhoea or constipation. Without treatment, between 12 and 30 percent of people infected with typhoid will die from complications such as intestinal perforation or haemorrhage1.

In most cases typhoid is transmitted when an infected human, who can feel sick or have no symptoms whatsoever (asymptomatic), contaminates food or water for consumption by others with faecal matter2. Between two and five percent of people convalescing from typhoid infection will become carriers, appearing well but able to transmit the infection to others, as was the case with the famous figure Typhoid Mary3.

Typhoid fever is more common, either endemic or in producing epidemics, in developing countries with poor infrastructure, so regions of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa in particular are significantly affected. As laboratory testing can be sub-standard or even non-existent in some areas, the number of cases worldwide is probably an underestimate of the true burden of disease. The Coalition against Typhoid uses various sources and calculations in putting the number of infections between ‘12 to 21 million cases and 128,000 to 223,000 deaths per year’4.

Worrying times

It was in 1990 when typhoid bacteria resistant to three commonly used antibiotics were first observed in India and nearby countries; one of the main reasons for their emergence is said to be from people self-treating with antibiotics. By 1996, when another antibiotic was added to the list of treatment failures, the spread of multi-drug resistance (MDR) and reduced sensitivity escalated, eventually being felt as far afield as the UK, Thailand, Mexico and Peru5.

One step further

One of the resistant strains that was discovered in the 1990s, known as H58, has adapted and spread faster, evolving into an extensively drug-resistant (XDR) form by 2016, when it was first identified in Pakistan. With the inclusion of a small piece of DNA, a plasmid, that is found in bacteria and in nature and can replicate independently, the H58 strain could reproduce quickly. As explained by the Coalition against Typhoid, ‘This is a troubling development because previous reports of XDR typhoid have been sporadic and isolated, while this particular strain has already caused a large-scale outbreak and is spreading within and outside Pakistan. It has already been carried as far as the United Kingdom: our colleagues at Public Health England detected this strain in a patient who had recently returned from Pakistan’6.

During an interview with a local news source, a senior doctor in the field of pathology and microbiology in Islamabad said there had been more than 2,000 cases of XDR typhoid in a 6-month period during 2018 in Pakistan and without new treatments ‘it could turn the clock 70 years back when surviving the disease was more a matter of luck than treatment’.

Current advice

In June 2018, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a travel advisory for Pakistan recommending that ‘Travelers to South Asia, including Pakistan, should take precautions to protect themselves from typhoid fever, including getting a typhoid fever vaccination’ and ‘…should also take extra care to follow safe food and water guidelines’.

Vaccines

From a pre-travel health point of view, vaccination against typhoid is recommended for travel to endemic regions, particularly to areas outside the usual tourist routes and for extended stays. Targeting particular groups of travellers is also important: children, the elderly, pregnant women, people visiting friends and relatives, and those with medical conditions that can increase the risk of infection (reduced stomach acidity or intestinal pathology relating to inflammatory bowel disease, surgery or cancer)7.

Two different types of vaccines used to prevent typhoid are available in Australia8: one, a live vaccine which is not suitable for all travellers, the other, an injectable form. Both are repeated after three years if there is to be continuing risk i.e. more travel to typhoid endemic or epidemic regions.

We would also encourage travellers to observe good personal hygiene and the careful selection of food and beverages. Drink only safe bottled or filtered water and avoid raw (undercooked) shellfish, salads, cold meats and ice in drinks.

In closing, we must add that, unlike hepatitis A infection, having contracted typhoid fever once does not protect you from another bout at a later date, so vaccination and following safe food and water guidelines remain your best methods of protection.

Before you travel, call Travelvax Australia’s telephone advisory service on 1300 360 164 (toll-free from landlines) for country-specific advice and information. You can also make an appointment at your nearest Travelvax clinic to obtain vaccinations, medication to prevent or treat illness, and accessories for your journey.

- https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/typhoid-paratyphoid-fever

- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/typhoid/en/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959940/

- http://www.coalitionagainsttyphoid.org/policy-advocacy-to-take-on-typhoid/how-to-talk-about-typhoid/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/nmi2.46

- http://www.coalitionagainsttyphoid.org/sequencing-a-superbug-how-typhoid-became-extensively-drug-resistant/

- http://www.antimicrobe.org/b106.asp

- http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/Handbook10-home~handbook10part4~handbook10-4-21#4.21.4