Talk to anyone born prior to the 1960s and they will tell you about how polio used to be a terrifying reality. Hundreds of thousands of children across the globe were left paralysed in its wake and confronting images of wards full of iron lung machines circulated. With the introduction of the Salk vaccine in the mid-1950s, polio outbreaks became less frequent – the last epidemic to hit Australia was in the early 1960s. By 1966, the oral Sabin vaccine came into use and this was replaced with a more effective inactivated vaccine in 2005.

About polio

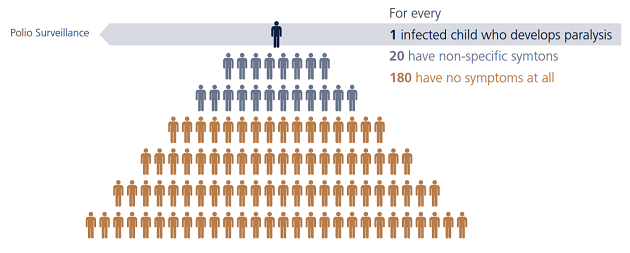

Polio is a potentially serious viral illness spread through contact with infected faeces or saliva. It is made up of 3 types of wild polio virus WPV 1, 2 & 3 – all of which can cause disease. Polio has a variable incubation period of 3-21 days. Infected individuals are most infectious from 10 days before to 10 days after the onset of symptoms. In 90% of cases, polio infection passes without symptoms but, if they are present, they include headache, fever, vomiting, tiredness, neck and back stiffness, limb pain with or without paralysis. Severe paralytic polio occurs as a complication of WPV in 1 in 200 cases. It affects the spinal cord in 79% of cases, which leads to acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) affecting the limbs (mainly the legs and is asymmetrical). Paralytic polio can lead to death in 2 - 5% of children and 15 – 30% of adults. There is no cure and treatment is supportive; immunisation is the only way to prevent infection.

The largely asymptomatic nature of polio is a major hurdle in the eradication efforts as authorities try to identify cases in often remote regions of the world.

Figure from Global Polio eradication initiative 2011 report http://www.polioeradication.org/

Eradication efforts

In 1988, the World Health Assembly (WHA) resolved to target polio with a view to achieving eradication by the year 2000 and formally founded the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). At the time the GPEI was established, more than 1000 children a day worldwide were diagnosed with polio. Since then, in excess of 2.5 billion children have been immunised against polio and there has been some success in eradicating certain strains of WPV: the last case of WPV type 2 was reported in 1999 and the last WPV type 3 in 2012.

By 2006 the number of WPV cases had reduced by more than 99% and only four countries showed no interruption in WPV transmission, namely Afghanistan, India, Nigeria and Pakistan. India was removed from the list of endemic countries in March 2014 and in October 2015 Nigeria was also taken off the list.

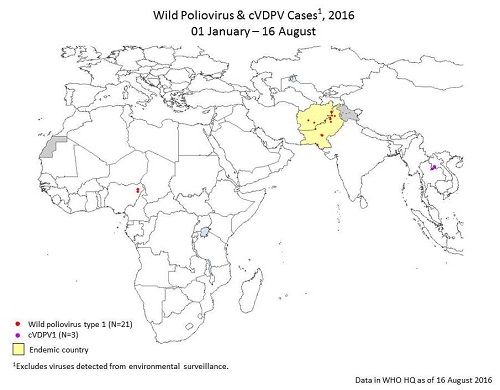

In 2016 year-to-date, there have been 22 cases of polio reported across the globe compared to 350, 000 in 1988 and until last week (11th of August) the only 2 countries reporting wild polio were in fact Afghanistan and Pakistan. But in a major setback to the global eradication campaign, Nigeria has notified the WHO that after more than 2 years without wild polio 2 children have been diagnosed with paralytic polio in the northern state of Borno.

Polio Global Eradication Initiative – Data and monitoring http://www.polioeradication.org/

It was in 2012 that the World Health Organisation (WHO) instigated the Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013 -2018 which outlined an all-inclusive strategy addressing how to deliver a polio-free world by 2018.

Successes

The Regional Commission for the Certification of Polio Eradication declared the WHO’s 11 country South-East Asia Region free of circulating wild poliovirus in March 2014 when India’s polio status changed. The region was the 4th of the 6 WHO regions to be certified as having interrupted all indigenous WPV circulation (the Americas in 1994, the Western Pacific in 2000 & the European Region in 2002).

Current situation

While the eradication programme has had successes, many factors stand in the way of reaching the eradication goal:

- The growing conflict and insecurity in the Horn of Africa and Middle East has played a major role in precipitating outbreaks in this area

- Increased instability in Pakistan, allowing continued transmission

- Disruption to immunisation activities in these areas has led to low population immunity and ongoing insecurity hampers the efforts to respond to outbreak reports

- Rapid detection of cases can be hindered in some areas by suboptimal surveillance

- Supplementary immunisation activities have had insufficient impact on stopping transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan – this is mainly due to poor planning which results in the same groups of children missing vaccine doses.

Recommendations for travellers

In May 2014, the WHO declared the international spread of wild poliovirus from endemic areas into polio-free areas a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ and instituted some temporary recommendations: currently these only apply to Afghanistan & Pakistan and require that residents are to be vaccinated against polio and supplied with an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Long-term travelers (staying >4 weeks) to the polio-infected countries may be required to show proof of polio vaccination when departing the polio-infected country. To meet these WHO requirements, long-term travelers should receive polio vaccine between 4 weeks and 12 months before the date of departure from the polio-infected country.

Australian children receive a primary course of polio vaccinations as part of the National Immunisation Program. For those adults who have completed a primary course and will be travelling to countries where wild poliovirus transmission still occurs, a single booster dose is recommended. However travel requirements do occasionally change in response to outbreaks, so up to date advice should be sought from your travel health provider or through the Australian Government Department of Health website.